“Notes from the Sandbox: On Art, Identity, and Everything in Between” Interview with Marc Dennis

By Leah Kogen Elimeliah

Marc Dennis, Where the Sun Hits the Water, 2021, oil on linen, 60 x 57 inches

To stand before a Marc Dennis painting is to encounter art that is both meticulously composed and wildly alive. His paintings invite the viewer to negotiate their own gaze, not just to look, but actually feel the life in the works using all five of our senses. For me, it felt like I was observing an artist whose true medium may, in the end, be “wonder” itself, because Marc doesn’t live within the confines of time or space, according to him, he is scattered across galaxies and reverberating through the digital age. His creative pursuits are unbound by gravity or clockwork. Instead, it feels like his art pulses at the intersection of the Renaissance and the Baroque. Take for example works like “Tradition,” “Big Love,” “Where the Sun Hits the Water,” or “Ironman, Captain America, and Batman Walk into a Bar.” With these works, Marc traverses stillness and motion, opulence and decay, historical longing and the fleeting now, all the while humming the dull aches of beauty. Though he is renowned for his hyper-realistic paintings, Marc doesn’t utilize the concept of “beauty” as a mere aesthetic choice. For him, beauty serves as a tool for exploration; a confrontation; and even, a cat and mouse game of seduction and subversion.

I went to see Marc’s studio in Chelsea where our conversation unfolded, touching on everything under the sun. Ideas bounced all around us, leaping from subject to subject. As we continued forming unexpected strands of thought, what emerged was a shared sense of artistic inquiry into what defines art, form, and context…not just in theory, but in lived experience. Our commonalities as artists were the foundation beneath a deeper dialogue, one that revealed the layered terrain where creative practice, personal narrative, and philosophical reflection intersect.

At the heart of his practice lies a profound devotion to the “Old Masters,” not so much as museum relics, but as living mentors who guide him through contemporary questions of identity, beauty, consumer culture, as well as historical and spiritual inheritance. Marc’s palette speaks fluently across time, threading Baroque drama into modern aesthetic, and lacing classical form with radical curiosity. His ability to paint vividly, with the use of bright colors and disrupted storytelling creates a radiant and immersive revelation for the onlooker. He uses traditional methods to break down classical modes of representation and the compositions that emerge are both inviting and most unexpected.

Marc’s life, much like his work, defies a linear narrative. From family stories of expulsion and immigration from Ukraine to Cuba, to America, to his diverse Jewish upbringing swaying between Hasidism and Reconstructionist Judaism, to his post-college life in a teepee on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in South Dakota, his journey has since unfolded across continents: Israel, Rome, Venice, Florence, Egypt. Each place he’s called home signifies a point on his inner map, a map that’s connected dots and provided him with a new cultural perspective to spark his imagination. Marc finds pleasure in asking questions. He marvels at and represents beauty in his work not as an escape, but a reckoning between the classical and the contemporary. His practice is about diving into ancestry, identity, and the continuity of time.

LKE:

I really love how your artworks tell multiple stories. You have built a metaverse within your art.

MD:

I was never determined to do that; I never set out to create meta-narratives in my artworks, but what I realized is that I am always making a painting within a painting, telling a story within a story, or multiple stories, sometimes even multiple paintings. I always liked the notion of a metaverse. I guess now I realize that I am that guy.

LKE:

Now you are meta within meta…

MD:

Now I am Marc within Mordechai, ancestral Haredi Jew. My Zaidy was Orthodox. I know my ancestors were probably Hasidic. I often think about the duality within my ancestry, being Hasidic and Reconstructionist, Haredi and Secular. One day I wear a kippah, another day a cap, some days a shtreimel or a hat.

LKE:

Can you share a bit about your family and your childhood?

MD:

Once upon a time, my father was studying to be a rabbi. He grew up Orthodox and was originally from Ukraine. He and his family escaped the pogroms by running to Cuba. Jews went there because America denied them entry. Then they had to escape from Cuba when Castro came to power. My family spoke Russian, Ukrainian, Hebrew, Spanish and Yiddish in the house. When my father was a student in Havana, but suddenly his family had to leave, that's when they moved to the U.S. Our cousins who were already living in Boston sponsored my father’s trip. My family’s original name is Detinko, but in Boston at the docks where immigrants were shuffled, a guy suggested having an Irish sounding name, and one that was similar to the Danis’, the cousins who sponsored them, so my Zaidy agreed to change the family name to Dennis.

LKE:

I know you are very much linked to your Jewish identity and even taught a class in Holocaust studies. Can you talk more about that experience?

MD:

After I graduated with a Masters, I was teaching upstate New York at Elmira College. I had asked the Dean if I could teach a class on the Holocaust because a lot of the students didn’t really know much and I was thinking of teaching a class on art that was made during that time. Not many people teach about this topic nor see beauty among an industrialized genocide. The Dean agreed and asked me to come up with the syllabus. “What's your interest?” He asked. I told him a story about the time when I was in Israel in 2000, when I went to visit Yad Vashem. There, I saw a little drawing of the moon. When I looked closer, it said “The Moon,” by Petr Gins. I later found out that he was a Czechoslovak boy of partial Jewish background who was deported to the Theresienstadt Ghetto. He died in 1944 at sixteen years old in Auschwitz-Birkenau concentration camp. I thought to myself, what is this? I didn't understand, I thought it was a modern day artwork by a Jewish teenager commemorating this guy Petr. I went up to the front desk and asked who made this artwork. I was told that these sketches and drawings were made by children during the Holocaust in concentration camps. There was a lot of art that came out from the camps, by many who were imprisoned, who were documenting what was happening to them there, of course this was all done in secret. Sometimes, Nazis asked the artists to make sketches or paintings for their homes or their wives, and in turn, the Nazis let them live a little bit longer. I asked the woman at the front desk about how the inmates got their art supplies, that’s when she decided to introduce me to the curator of the exhibition.

I went upstairs where I was asked to put on white gloves. There I spent three hours with the curator, holding drawings in my hands from Auschwitz and Birkenau prisoners, Dachau, Buchenwald…I couldn't believe what I was seeing. I was crying because it all felt very very real. That’s when I decided that I was going to teach a class on Holocaust art. The class was called “Hidden Under the Floorboards: artworks made by prisoners in concentration camps.” The prisoners didn't just make portraits of people, they didn't just make forced or commissioned works for a potato or an extra slice of bread, they also smuggled supplies to the barracks for others to draw, document their life, bearing witness to the torture, the deaths, the brutality. These were later on used in the Nuremberg trials. When I told the President of Elmira College about this he gave me the go ahead to teach the class. I taught it for many years. Now I get invited as a guest lecturer. Recently Cornell invited me so I taught there for a while.

Marc Dennis, Ironman, Captain America and Batman Walk Into a Bar, 2022, oil on linen, 80 x 61 inches

LKE:

I first learned about you and your art through a young gentleman I met at an Art World for Israel event in 2024. He told me you were his mentor. Can you speak a bit about how you got involved and formed a close relationship with this young Hasidic artist whom you have taken under your wing?

MD:

It started with Pinny messaging me on IG, asking to meet. I checked out his profile, thought, what the heck, maybe we are family, and Mishpucha matters — what if we are cousins. He came to my studio in Dumbo while other people were visiting me, they were of course curious as to why there was a Hasidic man in my studio. I was enamored by his desire to learn about art, wanting to draw, to paint. I bought him a book, My Name is Asher Lev. He said, "Why did you give this to me?” I said, “just read it, you could be the next Asher Lev.”

After our initial meeting, I started taking him to openings, exposing him to the scene. He draws well so I suggested he work alongside me. I bought him paint, canvases, and paint brushes. One thing led to another, and his community caught wind and came to visit me. Now some of those religious communities around Upstate New York and in Brooklyn want to open galleries in their neighborhoods, they want to learn how to draw and paint. Pinny is doing just that, he is teaching young Hasidic kids art classes, helping them utilize their minds, giving them space to think outside the box.

When Pinny first came to my studio, he asked about the big mezuzah hanging on my front door, which was given to me by the local Chabad. They were the first Jewish presence in DUMBO, soon after, they took me in similarly to the way I took in Pinny. I started putting on Tefillin, they put up the mezuzah in my studio, otherwise nobody suspected I was Jewish. In my house, in New Jersey, I have mezuzahs on every door. They are from a former Holocaust survivor who I befriended during the time I was teaching Holocaust studies. Once she passed away her family took down all the mezuzahs from her house and delivered them to me.

LKE:

Like I said, a story within a story, within a story. Tell me about the “Three Jews Walk Into a Bar” painting series which you exhibited at A Hug From The Art World Gallery in New York.

MD:

That has been going on for about seven years now, but honestly, it has been developing my entire life, my Jewish identity I mean, through my work. All my life I heard people asking me, “What, you’re a Jew?” “You’re Jewish?” “You don't look Jewish…” I thought about what they think Jews look like. I realized they must think Jews are the stereotypes that the propaganda in Germany and Russia used to describe what a Jew is. We have a certain nose, certain clothing, facial hair. So I thought to myself, I will make a painting about three Hasidic Jews walking into a bar, that doesn't happen very often. I thought why not own the joke if we are Jews who “own everything” — might as well own this. So if I am going to paint about my identity, about my ancestors, I started making the series, “Three Jews Walk Into a Bar.” As I said before, I come from a Haredi family, from the shtetls, my Fiddler on the Roof, as well as my secular upbringing. So I put all parts of myself together and it began to coalesce in these paintings. I knew I needed to have a sense of humor and that series of paintings was a response to that Art World movement — and people loved it. Many people loved it, including Hasidim who came down from very religious communities. The opening was a mix, perhaps 40% Hasidic, 40% other types of Jews and 20% the rest of attendees. Surprisingly, because many said the works are a hard sell, they nevertheless sold very well.

LKE:

Can we talk a little bit about you combining new with the old, looking back at old art and old style painters and connecting it to the modern day, it's quite prevalent to your work. Taking on the idea of consumption of images, how we perceive beauty, especially because the concept of beauty runs through most of your work, and the subversion of it, what does “beauty” mean to you?

MD:

It’s pretty simple really. Beauty is everything. Why would I want to pursue anything else? Beauty brings happiness, it brings smiles, it also speaks to a lot of what is happening in the world. I know that I don't want to add any more pain or stress to my life or to others. Life is meant to be lived. If I am going to reproduce life, to recreate it and make it my own through my art, then I want to experience beauty because it's not a “thing” it's an “experience.” For example, when I go to the woods and I see trees, birds, flowers, the sky, I am experiencing it. I want to give people a similar feeling, that they can either relate to or at least appreciate. Once I release my art, it's there, out in the world, I don't have any control over it, like nature.

LKE:

Can you talk about your process of coming up with titles for your works?

MD:

Once when I was teaching a class in college, I told my students that they all have to title their works. They were so uncomfortable with giving their paintings names. I explained this is all part of the creative process, maybe it's based on a feeling, a thought, something you saw. Some students said, “what if I don't want a title,” I said, then you better have a reason for it, because people will ask you why. Honestly, I also have a hard time with titles. If I go into a painting with a clear thought, that thought will be gone in a week of working, because I let my thoughts go…if there was an impetus to my work, I am not painting about that, I am mostly painting about a feeling. I sit with a painting for a day, a week, sometimes weeks, it could even be a year and then suddenly a title will come up. Unless the painting is part of a show and I am prompted by deadlines. But I try to add the whimsical side of myself and the fun side, so sometimes my titles are silly and playful. Sometimes I go through Shakespeare’s sonnets and like a word which then prompts the title, words like “swan” or “song.”

There was a time in my life, when I lived on a reservation, in a teepee; I rode a horse, had long hair, and was studying the Lakota Indian culture also known as Western Sioux. I had been interested in this culture since I was a teenager. I draw a lot of inspiration from ethnic cultures that are not my own. I used to go to pow wows and meet locals, and I had become friends with many from various tribes. One thing led to another, and I was invited to live with them, so I did. The word “clan” carries layers in its language. Word “skull,” an interesting word but I can’t use it in a title because immediately it will be skewed by people, the meaning of words in mainstream society have become limited. But I love digging into subjects and language and imagery, and that's what I appreciate the most about the work that I do. I love to play in the sandbox — why don't adults play in the sandbox more often, I never understood it.

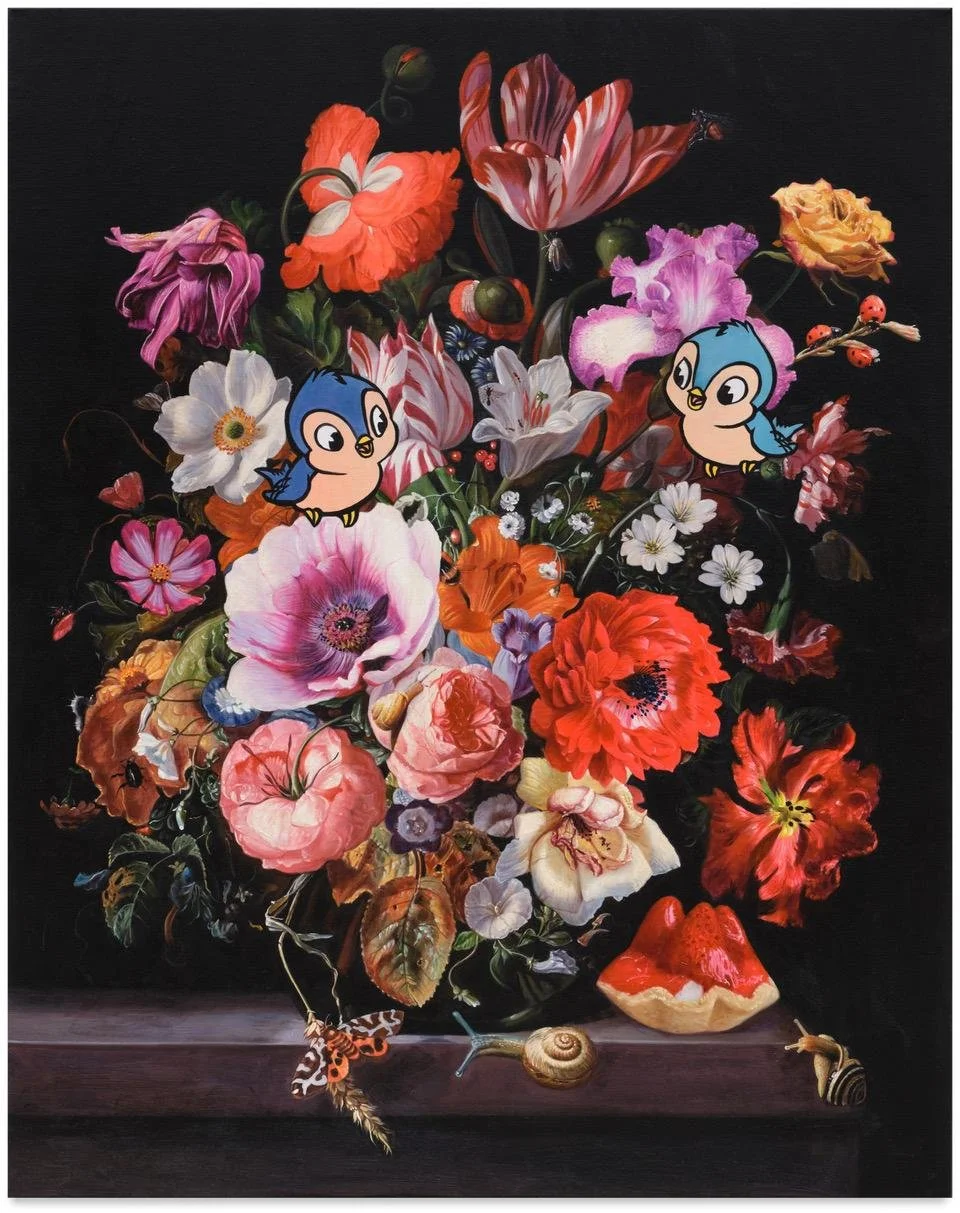

Marc Dennis, 2024, oil on linen, 40 x 30 inches

LKE:

What are your thoughts about how beauty is currently perceived in society, and what does that mean to you?

MD:

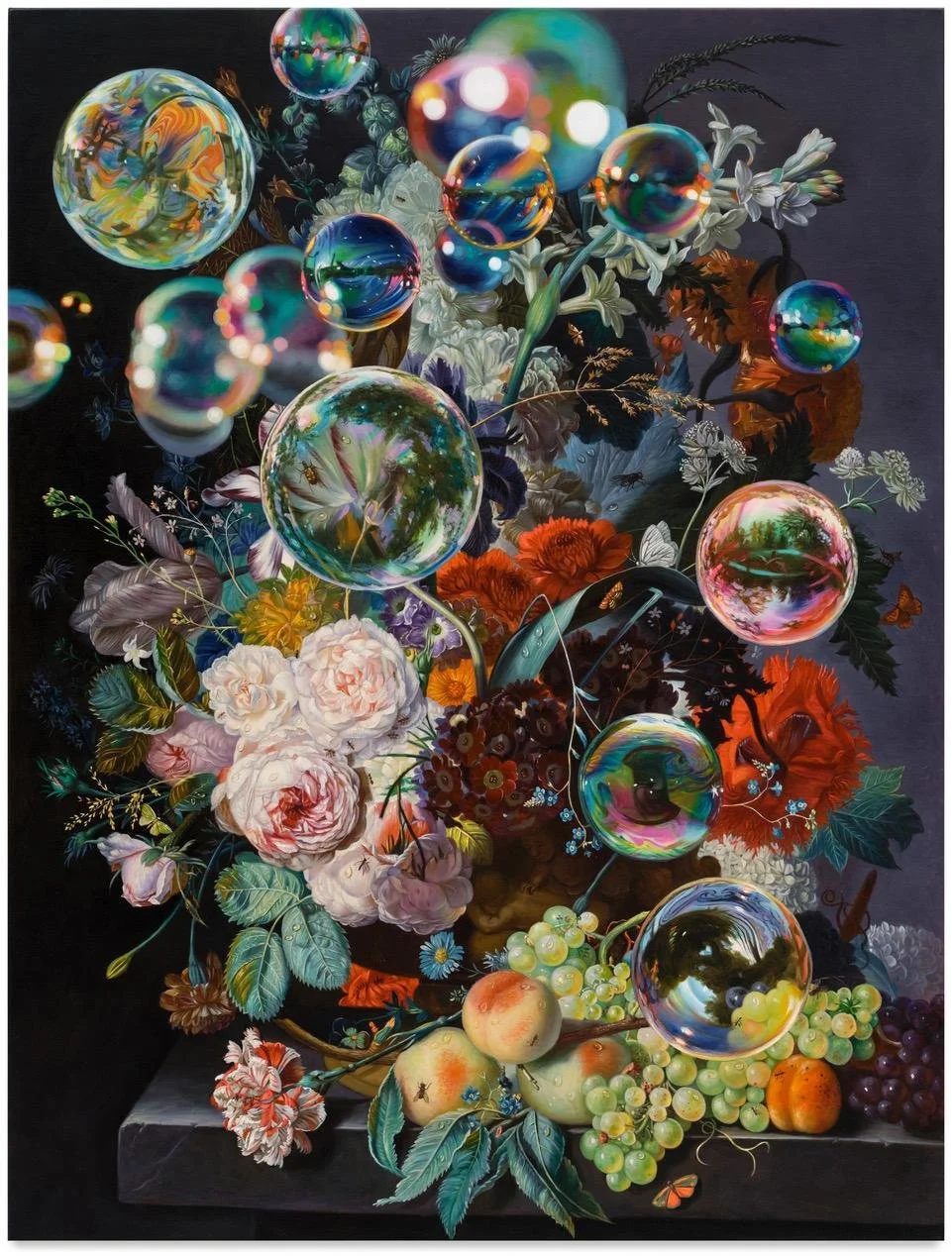

I don't really know how to answer that. To me it's all encompassing. For example, I love hockey, and I love going to games. When the lights go on, they are halogen, and it's nothing like you see in your house or elsewhere. But when the light hits the ice, I see translucent layers, I don't look at it as a surface to skate on, I look at the depth, I think of the way the light bounces off the red and the blue lines; that fascinates me and encompasses all my senses. I do have intentions, but if I can convey similar volitions and views that's a score, that's a touchdown. But there are many things I just don't plan out. I look at a bouquet from an old Dutch painting, sometimes by a German artist, or French, but mostly Danish or Flemish, because at that time flowers were a tool for currency, it was a status symbol. Then it became a religious symbol. Those paintings inspire me even though I don't know what is really going to happen in my own work.

And what happens to me in general is that my brain is always working. I imagine two angels sitting on my shoulders, one telling me “do it,” and the other saying, “don't do it…” and that happens to me pretty much all day long. When I am making decisions, that experience is even more amped up and what has to happen is I have to be very clear about what I am seeing in the bouquet and why I want to go in this certain direction, because the ideas in my brain are overflowing, there's too many possibilities and I need to focus on a single frame. So, for the past ten years or so, my frame has been flowers, particularly from the Dutch old master paintings, because I found in them a sense of intimacy that doesn’t exist in contemporary art or quite frankly most art. What I see in these old paintings is sensuality, depth, passion — I could hide things in there, and it allows me to focus.

LKE:

I see what you mean, however, you also provide this surreal feeling to them by layering your pieces with images that don't quite belong, like a squirrel or a blue birdy from a cartoon, or another silly character. What does that do for your work?

MD:

I always looked at the Old Master/New Master thing — for me there is a blurred line, and I want to be right on those lines, knowing I am part of the in between. Intrigued by old masters now I look at them and their works and say to myself, wow these are fresh, because they never died, they are real and alive. Tapping into my imagination while channeling the Old Masters is a way to make the lines tangible.

All artists have conceptions, the way they view the world. I have intentions behind making art. There are ideas but one must also have intention. What do I want to say with my work, how will I say it, and who is listening? My intention is based on feeling, the vibe, what I want to convey in terms of emotion. I don't want to make paintings that are political. But if politics are in there, then let it be. I have two teenagers so of course we always talk about what's going on. We talk about relationships, wars, about politics, about antisemitism — they have questions. Politics are everywhere, and if it's in my paintings, then in a symbolic way, let it be natural, let it form on its own. I want people to get to know me through my art and as you know, we all regenerate.

LKE:

Art regenerates…

MD:

Well, that to me is almost scientific or science fiction. Art is never about one pathway. I want nature, I want science, I want physics. But wars — why would I want to focus on wars?

LKE:

So pretty much culture and art are always in motion and some art, like the classics, even though there is less movement, are still essentially living, even in you. So, would you consider yourself a still life painter?

MD:

I cannot believe you just said that. I was just discussing this with my studio manager, Nicole, also a wonderful painter, and she said she sees me as a still life painter. I’m cool with the term, but I think my paintings are more like living landing places, for the viewers and even myself. It is yours for the time that you land on it and be part of it — become one. Stand in front of it, become one with it. I know it sounds weird…

LKE:

It's not weird at all, someone standing in front of a painting viewing it and someone else is viewing them, some call it voyeuristic, I call it contemplative. There is a mirroring, an exchange that is taking place in your works — a reflection. For example, one of your paintings has eyes all around, I am looking into them, they are all looking at me — there's an interception taking place.

MD:

Yes, for example, the bubbles in my painting are thoughts, like thought balloons, that are fleeting. I didn't want the work to be only with flowers, I wanted something that you can “see through,” so there's another sense of space. When my kids were younger and loved bubbles, I thought why not paint bubbles, that's not been done much before, and that's how that idea came, it’s that simple. So, there's your inspiration — life, parenthood, everything is inspiring. Me being a father is in the painting. Let me say the corniest thing I ever said in an interview; I paint about love.

Marc Dennis, Three Jews Walk Into a Bar, 2023, oil on linen, 66 x 62 inches

Marc Dennis, Tradition, 2025, oil on linen, 70 x 55 inches

LKE:

Well, it's fundamental to our existence.

MD:

I know but I have never said it.

LKE:

Well, you have now, you have confessed to us, transformative possibilities…I have been waiting to ask the most important question of all — your thoughts about the art world. Where do you think the art world is going?

MD:

I have to obliterate the term “art world.” It's more like an art galaxy. First and foremost, the egos. Artists, writers, curators, collectors, we are all those particles floating around. We all have the ego, I have it, it might not be big, but it's there…we are all hungry, we all like to feed it. I know I like to feed it. As far as the “art world” and being part of something, there are many planets to touch upon. You need to find your inspiration and then find your place to land. I found mine when I was young. I wanted to be in the canon of artists who weren't just dedicated to their craft but who responded to the notions of beauty and history, and I wanted to be in New York. Granted, paintings for the first three, four hundred years were mostly religious, because that's where the artists got the money. No one went to the studio back then and said let me just make a painting. No, they waited for commissioned works — the wealthy clients, the Pope, the Church, the dukes and duchesses, the kings, and queens – they all had the money to commission works.

I don't mind being an artist who will do commissioned work two to three times a year. I don't have a problem with that. If I make a really nice connection, and it doesn’t violate my aesthetics and I have the time. why not? There are also artists who don't mind showing their works in the local library or they are off painting in a cabin in Vermont and they are happy. They are smelling the linseed oil, same smells as here other than the food carts on the city’s sidewalks, but it's what one chooses for themselves. People make art in the hills of Umbria and they are happy, they are making art just like me. They simply may not be interested in the New York art scene. Artists need to find a place where they are most motivated to make their most effective work and sense that inspiration is near. New York City is where I wanted to be, in the scene and be seen, because I have a healthy, hungry, happy ego. But to answer your question though, there is no art world. There is just art in a massive ever-expanding universe of opportunities. And then there's particles.

LKE:

I understand but as an artist who is observing everything that is happening around you in the art world, even if you are not part of it, since you are in another galaxy, in terms of PC, DEI, being silenced in art whether by societal expectations, the government or public opinion and what sells — how do you survive and attempt at living in that sphere as an artist?

MD:

I love your questions. This is a great one and I have a great answer for you. Here is my deal; I taught college for sixteen years. I had parents come to me and ask “why is my child suddenly changing majors? Why does he or she want to suddenly be an artist?” I had many students who were bio majors, history majors, even pre-med who suddenly wanted to learn how to express themselves through art. So they took my classes and got inspired. Will they become famous artists, successful artists, probably not, but the parents would ask, “is there anything I can say or convey to my child career-wise, or is there a key to success if they choose art as their career?” And my answer was always “There is no key to success in the art world, but there is a key to failure, which is trying to please everyone all the time.”

About twenty years ago the art and museum universe began to shift. It's like my grandmother used to say, “Marc, remember, everything in moderation, don't go too far in any direction.” Growing up, there were five of us, all boys, all one year apart, and we were quite active and often rowdy, and looking back I know where my grandmother was coming from — she wanted to make sure we didn't destroy anything in the house and stop running around and to find moderation in our behavior. I accepted her advice as I pursued that idea of balance throughout all parts of my life, especially as an artist. I recognized that the perception of art, the need for balance in who and what was represented and the gallery scene was shifting. Trying to find that balance within institutions, figuring out what to exhibit, people started bringing up statistics about demographics, who is not being shown, who is on the margins, less artists of color, less women; it drove much of the aesthetic and market structure. I stayed true to my game all the while respecting the plate tectonics in the industry but always holding onto my grandmother’s mantra, “…everything in moderation.”

Staying true to one’s game is the best way to play. As I said, you cannot please everyone all the time. I accept the ways of the world. There are words of wisdom by Max Ehrmann in Desiderata which he wrote in 1927, that you must find ways to surrender to things you cannot control, to find serenity in the things that you can. That is me, I am happy with the people who are buying my paintings, I don't need everyone to love me or my art. I know who I am.

LKE:

What role does the concept of time play in your work? The new vs the old?

MD:

My life is pretty abstract, I don't really live according to time. The only period in my life where I manage time is when it has to do with my kids — I need to make sure it’s all in my calendar or secured in my brain – the pick ups, the drop offs, their activities, voice lessons, going to the theater, games, practices, dentist appointments, etc. But to me personally time is quite abstract.

LKE:

We talked about your pieces being timeless so from that perspective, any reflection that comes to mind?

MD:

I’d like to think that I am painting moments, there's no beginning or end, there's no middle — it's just moments in time. My whole life I heard things like, “don't waste your time,” “you are wasting my time,” “time is running out.” I don't want to live in that kind of time frame. I don't want to think in those terms. If my thoughts are endless, and my ideas are endless, and love is endless then in a sense life is endless and I want to embrace that outlook. It may be overly idealistic but it’s imaginative and fulfilling.

LKE:

In one of your previous interviews, I heard you talk about not really having an interest in making sculptures. Why?

MD:

I realize I can't be focused on a sculpture; there are too many sides — I can only focus on one side at a time, one plane at a time. I get easily distracted. Painting is one-sided, one plane to deal with. It works for me.

LKE:

Well, in the same interview when you spoke about not wanting to make a sculpture you said you ended up making a painting of a sculpture.

MD:

Yes, that is what happened, the idea from that interview from ten or so years ago gave rise to making a painting of a made-up sculpture of flowers. People loved it and were puzzled by it when I showed them an image of the painting on my phone or ipad and everyone thought it was an actual sculpture of flowers because of my hyperreal technique. They wanted to know how big the actual sculpture was. I would tell them it's a painting they’re looking at, not a sculpture and they couldn't believe it. I loved that experience, I like knowing my works were trompe l'oeil on steroids. playing around with the idea of perception, foolery, trickery — I want the sandbox effect.

LKE:

Speaking of perception, how do you feel about the art world’s response to what happened in Israel on October 7th?

MD:

I understand why people are wary of speaking up because the trend is to balance, to do the right thing according to the masses, which I think is the wrong way to go. I have always done the opposite; though not in my art but most certainly in speech. If I could make one change when speaking to the people who shout “Free Gaza,” it's that I would add, “Free Gaza from Hamas.” Truthfully, it comes down to just freeing the hostages. If the hostages were freed let alone never been taken, the situation in that region would be very different. Hamas started it and they had the chance to end it. In my estimation and I’ll leave it at this – we Jews are sick of being fucked with throughout history and we should never let it happen again. Just as other races, cultures and societies are proud of their heritage and world contributions Jews are done with the bullshit. I’m personally done with all the bullshit; all the hatred, intolerance and racism, towards so many others for their culture, sexuality etc. It's no wonder we are becoming increasingly insulated.

For me the core of Judaism is to ask a lot of questions. I remember in school, especially Sunday school at the local temple, my mom was told that I asked too many questions, that it was disruptive to the class as a whole. But I wanted to learn, I wanted to know so much more. I still do. I have been an observer as early as I can remember, I have always remained curious about most things with a desire to grow. And of course, as an artist, a teacher, friend, son, brother, uncle, cousin, and by far most importantly as a father to my two kids, I strive to connect with all that is good and productive through art and love. Afterall, that’s how we learn to accept one another, to bring change to the world, spread happiness, provide hope and manifest peace.

Marc Dennis is represented by Harper’s Gallery, New York, NY; and Anat Ebgi Gallery, Los Angeles, CA. He divides his time between New York City and Montclair, New Jersey.